EdSource

As California faces increasingly destructive wildfires, schools should develop more preventative safety measures, experts say.

Roughly 12.6% of California public school students attend a campus located in high or very high Fire Hazard Severity Zones, an EdSource analysis of data from Cal Fire and the Office of the State Fire Marshal found. Those are often home to dry vegetation, steep slopes and dry, windy weather.

Even more schools, 13.7% – 1,459 of the 10,591 public schools across the state — are located in or close to a Fire Hazard Severity Zone, a classification that reflects general wildfire behavior in the region, and is different from fire risk, which gauges the likelihood of a fire sparking under a specific set of conditions.

Fire risk spans the entire state, from rural to urban areas and from north to south. But nearly 70% of students in high and very high fire hazard severity zones are in Southern California, where urban density meets fire-prone conditions.

One school within the Westside area landed on the list. Romero Elementary, which is part of the Gustine Unified School District and located in Santa Nella, was identified as having a moderate risk.

“Part of it is that those areas are denser [in population],” said Nicole Lambrou, an assistant professor of urban and regional planning at Cal Poly Pomona. “But I also think the bigger issue might be that there has been increasing development in the wildland-urban interface, which is more fire-prone. Land development patterns, driven also by increasing housing costs within … L.A. and the Bay Area, make development in formerly undeveloped [wildland-urban interface] areas more feasible as well as more desirable.”

The Office of the State Fire Marshal (OSFM) classifies Fire Hazard Severity Zones as Moderate, High, or Very High, based on factors like fuel load, slope, fire weather and wind patterns that increase wildfire spread. This classification reflects hazard, not risk — focusing on long-term wildfire behavior (30-50 years) without considering mitigation efforts like home hardening or fuel reduction.

With fires of serious magnitude becoming increasingly common, particularly in populous regions like Los Angeles County, experts say it’s time for schools to develop proper safety plans — and if possible, make their physical campuses more resilient against future blazes.

“Los Angeles, historically, was a pretty dry area. And through the decades and centuries, we’re now an urban community that had not experienced wildfires like this, like the Eaton and the Palisades fires, especially at the same time,” said Jema Estrella, the director of facilities and construction at the Los Angeles County Office of Education, in an interview with EdSource. “Because we are seeing these events more regularly, then we have to look at these lessons, and we have to consider what are the actions that we have to take on?”

In the 2018 Camp Fire, four schools were destroyed and nine had extensive damage. This year, the Palisades and Eaton fires in Los Angeles County damaged or destroyed nine public and charter schools.

Physical infrastructure

Hardening campuses — a process that makes physical school buildings and the landscaping around them less prone to fire damage — is one step schools and districts should consider if they’re presented with an opportunity to rebuild or revamp their current infrastructure, experts say.

“We have facilities that are brand new, that have all of these elements embedded,” Estrella said, referring to campuses across L.A. County. “We also have schools that are in older facilities, and that may not necessarily be so easily upgraded.”

Schools can use money from Proposition 2, passed by voters in 2024, for fire safety improvements. The measure authorized the State Allocation Board to help with disaster assistance.

Additionally, “school facility projects funded by Proposition 2 must meet applicable building code requirements reviewed by the Division of the State Architect for structural safety, fire life safety, and accessibility,” added a spokesperson from the Office of Public School Construction. “School facility design and material choices beyond building code requirements are determined at the local level by individual school districts and are typically considered eligible expenditures for Proposition 2 funding.”

To harden a campus, schools should consider certain non-combustible materials, including in their roofing, Estrella said. Dual-pane windows, she added, can also help prevent embers from flying into the building.

Beyond buildings, Estrella stressed that school grounds should be clear of vegetation or any highly flammable materials. Trimming trees and maintaining landscaping are critical to making sure foliage stays green and less susceptible to fire damage, she said.

Lambrou, the professor at Cal Poly Pomona, also said schools should consider designing “clustered campuses” — home to multiple buildings and, naturally, fire breaks between them.

Within campuses, experts have also stressed the importance of having proper air filters to preserve air quality and keep students and staff as healthy as possible.

“It’s also important afterwards, when there’s all this kind of debris filtering, and processing that’s happening that can stir up a lot of things,” Lambrou said. “During that time, kids tend to go back to school if the school is still standing, so having filtration is super important.”

Communication and planning

When the Eaton Fire set Altadena ablaze on Jan. 7, residents in certain areas did not receive evacuation notices — or received them late. While schools don’t play an active role in community evacuations, experts say adequate planning by school districts is paramount to everyone’s collective safety.

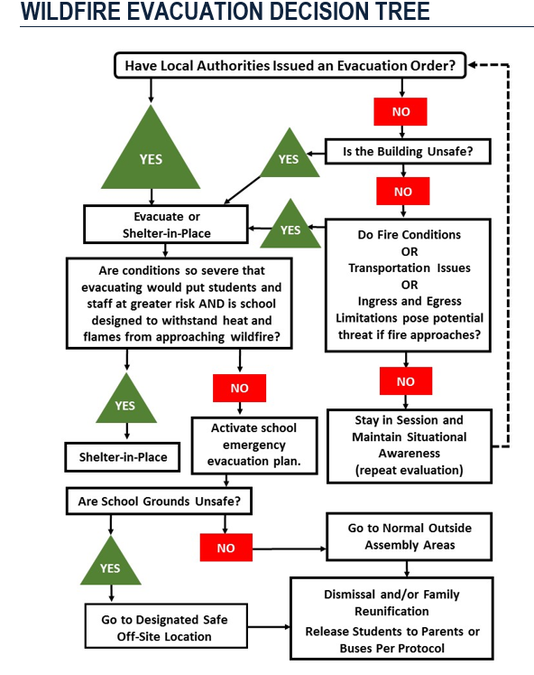

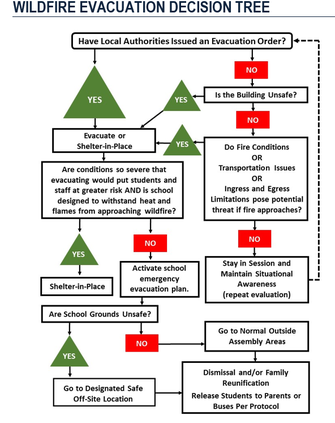

To help districts with planning, the San Diego County Office of Education (SDCOE) has provided local schools and districts with a template that they can customize to their needs, according to Tracy Schmidt, SDCOE’s senior director of attendance, safety and student engagement.

“When should you consider moving outdoor activities indoors? When do you potentially need to consider a closure … not due to the threat of a fire, but due to air quality?” Schmidt said. “So, it has those types of indicators and conditions. And then, how would they communicate this type of information to their community?”

Beyond planning, Schmidt also emphasized the importance of training for local educational agencies — something SDCOE has been participating in with the help of Cal Fire, the American Red Cross and the San Diego County Office of Emergency Services.

Lambrou said in the event of a wildfire, communication is also essential, particularly when it comes to potential evacuations and reunification of parents with their children.

“My daughter’s school burned down in the Eaton Fire, and we’re so lucky that the fire took place in the evening, that the kids were not in school because they were really high up there … pretty close to the foothills. It would have been nearly impossible to get to her,” Lambrou said, reflecting on her own journey during the January fires in Los Angeles.

On a broader level, “communication did not take place. It was very confusing for a lot of people,” she added. “Residents had that same issue, and they had to rely on each other.”

EdSource data reporter Daniel J. Willis contributed to this report.