Thanks to adequate water supplies and mild conditions throughout the growing season, California farmers may end up with way more tomatoes than canneries need.

The larger-than-expected crop means some of the fruit may go unpicked if the weather remains dry and harvest goes as planned.

“It’s a very excellent problem to have,” Mike Montna, president and CEO of the California Tomato Growers Association, said of what’s been described as a bountiful and quality tomato crop.

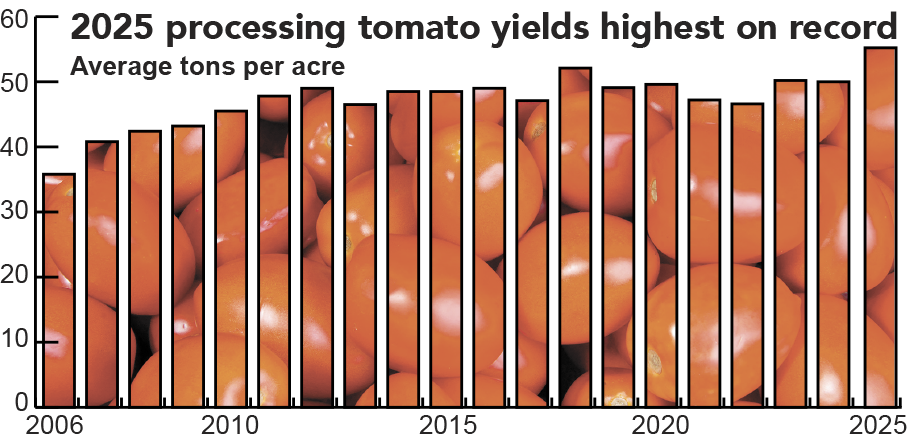

Cooler temperatures this summer have helped boost tomato yields to record-high levels, with an average of 55 tons per acre, according to a report released late last month by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The previous record of 52.1 tons per acre was set in 2018.

Even though canneries trimmed contracted acreage this year by 10% to a projected 200,000 harvested acres, total production is expected to reach 11 million tons, or 1% below last year’s 11.1 million tons from 221,800 harvested acres, USDA reported. The current projection is 7% higher than what was forecasted in May. This year’s 200,000 acres represent the lowest contracted on record going back to 1975.

Montna said some processors may take excess tomatoes if they think they can market more product, but they’re committed to taking only what they’ve contracted.

“We might end up disking some up, maybe not,” he said. “We’ll just have to see as the season plays out.”

If the weather holds, Montna said he expects harvest will go until mid- to late October, though volumes of late-season tomatoes will drop. Early fields began harvesting the first week of July, USDA reported.

Colusa County grower Mitchell Yerxa, who serves on the board of the grower association, said tomatoes aren’t the only crop seeing upticks in yield, noting his other row crops—including vine seed, cucumbers, watermelon and sunflowers—also have benefited from the weather this year.

But with several more weeks of harvest, Yerxa stopped short of calling the growing season perfect and making too much of “an above-average crop across the state.”

“We’re all very pleasantly surprised at how good the yields have been,” he said. “But there’s still a long ways to go for a lot of us. We all know how fast this weather can change.”

Yerxa said canneries in his region had bought excess tonnage from growers in the past, but that was likely to backfill production shortfalls elsewhere.

With growers in the Sacramento Valley harvesting 10% to 15% more than their contracted tonnage, Sutter County farmer David Richter said, “there will be tomatoes disked under unless something changes.”

He contracted to deliver 55 tons per acre, and he said three of his early fields have yielded 75 tons per acre—a record for him. He said he has heard of neighboring farms delivering yields as high as 80 tons per acre, which he characterized as “very unusual.”

While some canneries may accept more tonnage than was contracted, Richter said “there’s a huge reduction in price for extras because canneries really don’t want them.”

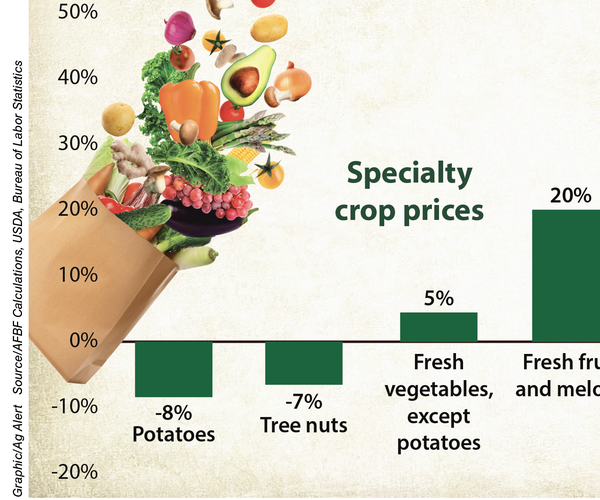

The negotiated base price for contracted tomatoes is $109 a ton for conventional and $137 a ton for organic, down from $112.50 and $145, respectively, last year.

Because of the larger crop, Yerxa and Richter said the harvest schedule set by processors has been running behind, as it takes longer to get through each field. Richter said he expects yields in some of his later fields will start to decline. He’s set to harvest his last field Sept. 20.

After consumption of processing tomatoes and other canned goods spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic, Montna said the industry is still adjusting to the post-pandemic “new normal,” as consumer eating habits have changed.

Responding to the surge in demand during the pandemic, which zapped tomato inventories, canneries contracted more acres in 2023—some 254,000 at a record-high price of $138 a ton for conventional and $190 a ton for organic. Growers delivered more than 12.7 million tons of tomatoes that year, an all-time high.

“While COVID wreaked havoc on many industries, it brought higher margins to California’s processing tomato industry,” said Matt Woolf, a specialty crop analyst for Terrain, a part of Farm Credit Associations, in a 2024 report.

But product movement during the past two years has stayed “relatively flat,” Montna noted, necessitating the reduced acreage this year to get “inventories a little bit back in line.”

Except for the early years of the pandemic, U.S. per-capita consumption of processing tomatoes has been declining since the 1990s, Woolf reported. And the downward trend will likely continue “as the pandemic fades further into history,” he wrote.

Fresno County grower Bret Ferguson, who also serves on the grower association board, said it’s not just changing diets that have eroded sales of processing tomatoes. He pointed to the struggling fast-food industry, a major buyer of ketchup and other processing tomato products.

“They’re mindful of the cost of the product, and they’ve cut back,” he said, noting how fast-food chains in his area no longer generously give out handfuls of ketchup packets with every meal.

With contracted tomato acres down, Ferguson said he has left more ground fallowed because commodity prices for corn and other grains also are down. Processing tomatoes remains a good option for growers who can get a contract, he said, though he expects contracted acres will shrink another 5% to 10% next year.

Despite stagnating domestic consumption, Montna said export demand has remained “relatively consistent.” To open and grow new markets, he said the association has been working with the Trump administration to offer comments “on markets that we think might be beneficial” to processing tomato growers.

But grower Ferguson said he doesn’t believe the sector can “export its way” out of an inventory problem, considering other tomato-growing regions around the world also have produced sizable crops in recent years. He said the high value of the dollar remains an obstacle for expanding export growth.

“It’s so cost prohibitive,” Ferguson said.

Ching Lee is editor of Ag Alert. She can be reached at clee@cfbf.com.

Courtesy of the California Farm Bureau.