BY VICKY BOYD

Ag Alert

Red leaf blotch has spread rapidly from a few San Joaquin Valley almond orchards in 2024 to throughout the state this season, showing the fungal disease’s formidability.

“Red leaf blotch is such an aggressive pathogen that it’s a game changer,” said University of California Cooperative Extension plant pathologist Florent Trouillas. “But we’re hopeful that we can control it at satisfactory levels.”

In severe infections, red leaf blotch can defoliate trees and reduce yield potential if left unchecked. But several registered fungicides are effective against the fungus, which infects only almond leaves.

In field trials this season, Trouillas screened 22 different registered products applied a total of three times: at petal fall, two weeks later and five weeks after petal fall.

“The pathogen is so aggressive that the priority is to find tools that can keep the disease as low as possible,” Trouillas said.

The most effective products came from Fungicide Resistance Action Committee groups 3+7, 3+11, 7+11 and FRAC 3-triazoles.

As with any disease program, he said growers should rotate effective modes of action to avoid resistance from developing. Many of those same fungicides also target other almond diseases, such as shot hole, scab, rust and anthracnose, allowing growers to manage several issues with the same treatment.

Based on discussions with colleagues in Spain, where the disease is endemic, along with UC research, Trouillas recommended a three-spray program for high-risk orchards. This season, a grower across the road from the UC trials made only a single fungicide application.

“It looked very good until the end of May. Then disease started showing up,” he said. “That shows a single application won’t stop the disease. We know that one is not enough. We know that two is minimum, just from observations. But that’s the big question. Three is to be really on the safe side, and with two, you may take a risk.”

Trouillas said he hoped to conduct a field trial in 2026 to compare the efficacy of two sprays versus three sprays to see whether growers could reduce applications without economic damage. He also planned to examine the intervals between treatments to see if they may be stretched.

“We want to fine-tune it because we know growers are on a budget,” he said.

Andrew Malagon, a pest control adviser with Precissi Ag Services in Stockton, said he saw the disease this season in the northern San Joaquin Valley, especially in parts of Merced and San Joaquin counties. From talking to growers, Malagon said, many of the worst orchards didn’t receive petal fall sprays.

“If you’re not following the petal fall two-week and five-week postpetal fall sprays, it seems to be correlated with this disease,” he said. “We had some growers that did two, and some did one. I know those that did one definitely saw leaf blotch.”

In some of the worst orchards, Malagon said the trees were so defoliated they looked like they’d already entered winter dormancy.

Ben Duesterhaus, a PCA with Mid Valley Agricultural Services in Linden, said red leaf blotch was common this season in the regions of Merced, Stanislaus and San Joaquin counties that the company serves. What surprised him was how quickly the disease dispersed after it was first found in 2024.

Duesterhaus said he frequently saw more severe cases this season in which growers may have reduced or eliminated petal fall sprays.

“This is new,” he said. “It spread quicker than expected, and I think that kind of caught everybody off guard, so I could understand their hesitancy (to spray).”

In making grower treatment recommendations, Duesterhaus said he looked at Trouillas’ research and findings from Spain, which seemed to closely match what he saw in California fields.

Caused by the fungus Polystigma amygdalinum, red leaf blotch is only a foliar disease. The five- to six-week period after petal fall is when leaves are growing the fastest.

It also coincides with when the red leaf blotch fungi produce the most infectious ascospores and spring rains disperse them, Trouillas said, citing data collected from spore traps this season.

To show the pervasiveness of the organism, he said he trapped 250 spores per square inch of leaf per week in a severely infected northern San Joaquin Valley orchard this season.

“That’s pretty extreme among orchards,” Trouillas said. “If you don’t do anything, the orchard is going to be completely burned out by the disease.”

He was referring to the severe defoliation the organism can cause. In fact, many trees in the orchard where he’s conducting trials experienced severe leaf loss last season due to red leaf blotch.

The goal of fungicide sprays is to protect developing foliage from fungal infection. Once infection occurs in untreated leaves, symptoms don’t develop until 35-40 days later. By then, he said, it’s too late to treat.

“The general approach for disease management is prevention is always key,” Trouillas said. “When the symptoms appear, you’re not going to eradicate the disease from the leaves.”

As leaves mature, the cuticle layer hardens, eventually protecting them against red leaf blotch infection.

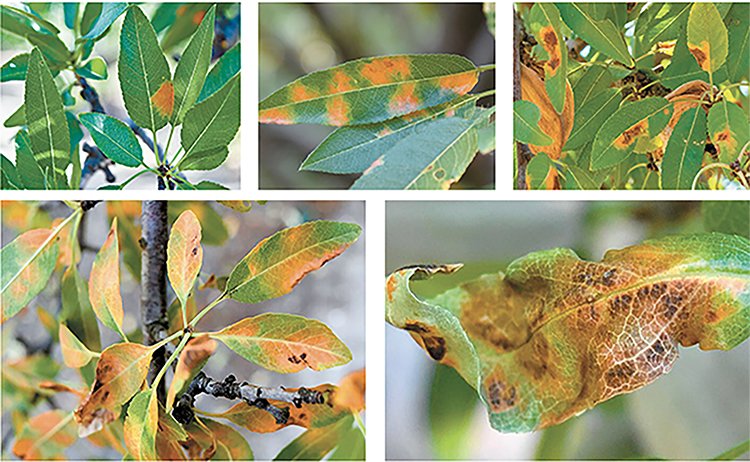

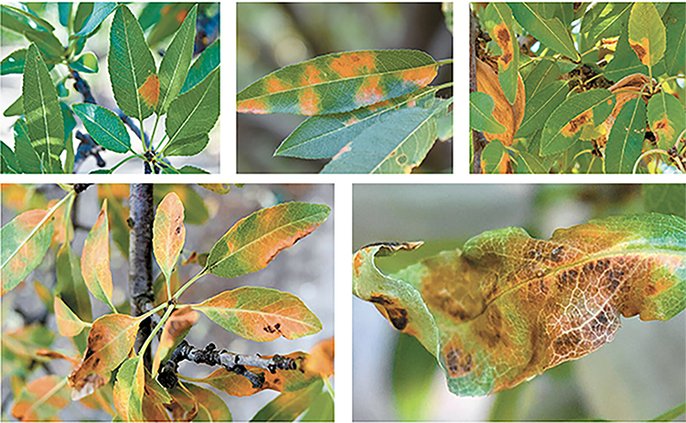

Initial symptoms include small yellowish spots on both the upper and lower sides of leaves. As the disease progresses, the blotches grow in size and turn reddish and then brownish. They also may coalesce to cover larger portions of the leaves, causing necrosis and premature leaf drop.

In severe cases, leaf loss significantly reduces photosynthetic capacity, impairing carbohydrate accumulation and ultimately reducing yields.

The organism has only one life cycle per year and overwinters as perithecia, or fungal fruiting bodies, on infected leaves that fell the previous fall.

Red leaf blotch was confirmed for the first time ever in California in 2024 when it was found in a few orchards in Merced and Madera counties in May. It is native to the Mediterranean and Middle East.

A handful of additional orchards in Stanislaus and San Joaquin counties were confirmed with the disease later in 2024.

Partly due to heightened awareness, numerous growers and PCAs this season alerted local farm advisers of suspected red blotch infections. Trouillas said the disease has now been found in nearly all the state’s almond-producing counties, from Kern in the south to Butte and Colusa in the north.

Vicky Boyd is a reporter in Modesto. She can be reached at agalert@cfbf.com.

Courtesy of the California Farm Bureau.