On September 11, the basement of the Newman Museum buzzed with energy as members of the Newman Historical Society, community residents, and representatives from the Newman-Crows Landing Unified School District gathered to discuss an ambitious project: bringing back the first motorized school bus in California history.

The discussion was led by Korey Santor, a teacher at Yolo Middle School and longtime supporter of local history education. For the past decade, Santor has involved students in National History Day projects that often highlight Newman’s unique past. Recently, with extra time on his hands, he dug deeper into the story of Newman’s role in transportation history.

His conclusion was striking: Newman is undeniably the birthplace of California’s first motorized school bus.

“This isn’t just rumor or legend anymore,” Santor explained. “Without a doubt, no exception—there’s only one birthplace, and incredibly, Newman is it.”

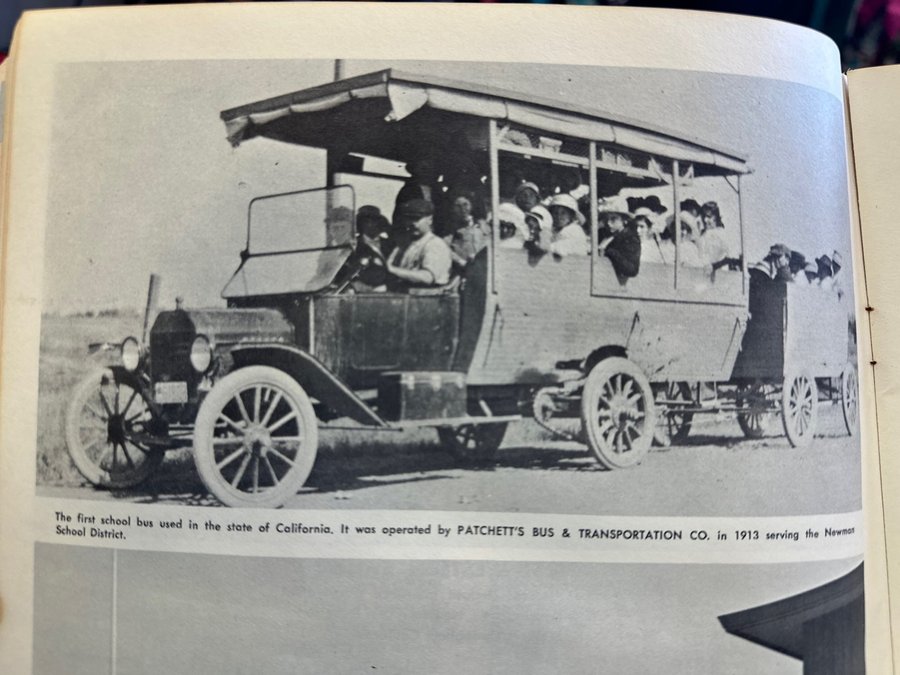

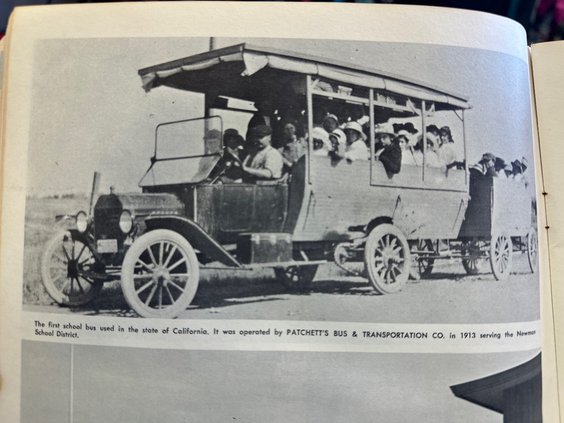

The original bus, built on a Model T chassis, was no ordinary school vehicle. To accommodate extra students, a hay wagon was attached to the back for boys to ride, an unusual setup that became the source of plenty of small-town stories and laughs.

Over the years, the bus slipped out of local hands and eventually to First Student, a national transportation company. Today, it is believed to sit largely unused in storage, occasionally displayed at trade shows.

“There are rumors about where it is and who controls it,” Santor noted. “But what seems clear is that it isn’t being used—and it isn’t in Newman, where it belongs.”

Some in attendance recalled past efforts to keep the bus in town. One member recounted how a former city official had reached out to Newman’s leadership years ago to see if the city wanted it, but no response came back. The bus was sold instead.

Given the uncertainty surrounding the original, Santor proposed an alternative: building a replica. His idea is to create what he called a “retro mod”—a vehicle that looks historically accurate on the outside but uses modern technology under the hood to make it safe and practical.

“Has anyone here ever driven a Model T?” Santor asked, sparking chuckles around the room. “They’re interesting, let’s put it that way. In 20 years, no one will even know how to drive one. If we want this to be usable, we have to modernize it.”

The replica, he suggested, could serve multiple purposes. It could become an icon for the town, available for use at parades, Historical Society tours, school events, and community celebrations.

“Imagine putting people on this bus and driving them around Main Street while they listen to stories about Newman’s past,” he said. “It wouldn’t just be a museum piece—it would be living history.”

A recurring question throughout the meeting was where such a bus would be stored and who would be responsible for maintaining it.

Newman Crows Landing Unified Superintendent Justin Pruett noted that space might be available on properties tied to the school district or nearby facilities. “We can store it easily,” he said, though he admitted the bus’s size would determine final arrangements.

Others emphasized the importance of securing long-term stability. Some argued for a shared ownership model between the school district and the Historical Society. That way, neither a change in school leadership nor turnover in Historical Society leadership could jeopardize the project’s future.

“It’s about preserving the idea so it doesn’t get lost when leadership changes,” one attendee commented.

Not everyone was ready to move on from the original bus, however. Several members pointed out that the City of Newman has been working quietly with First Student to see if the historic vehicle could be donated back.

“Why not pursue both?” shared Glennis Kidder. “The Historical Society and the city can continue trying to reclaim the original while the school district and community work on a replica. Just imagine the day when both are driving side by side in a parade—what a statement that would be.”

The idea of student participation generated excitement during the meeting. Santor proposed involving the high school’s shop classes and using the project as an educational opportunity.

“The high school requires service hours from students,” he said. “Why not tie those hours to this? Students could help with fundraising, researching stories, or even assisting in the building process. It connects them to their own history.”

Several attendees, including former bus drivers, noted the symbolic importance of engaging the younger generation. “If we give kids something meaningful to work on, they’ll carry it forward,” one member said. “That’s how you grow the next generation of Historical Society members.”

The meeting also touched on the realities of funding such a project. Professional restorers and metal fabricators may need to be hired to ensure safety and authenticity. Costs could run high, but Santor expressed optimism about modern fundraising tools.

“With digital fundraising nowadays, you’d be surprised how much can be raised,” he said. “If we promote it right, this could be totally funded—with even a little nest egg for maintenance.”

Still, Historical Society members cautioned that any fundraising effort must be clearly defined so as not to interfere with other ongoing projects.

In the end, participants agreed the idea was worth exploring further but needed more concrete planning before commitments could be made. The group discussed forming a committee to develop detailed proposals, budgets, and timelines, and to determine how the Historical Society, the school district, and the city might best collaborate.

While no final decision was reached, there was a shared sense of pride in Newman’s unique history and enthusiasm for finding a way to celebrate it.

“The only thing I can say is that if we don’t try, it won’t happen,” Santor concluded. “If we do try, even if we fall short, we’ll have at least made an effort to honor what makes Newman special. And if we succeed, we leave behind something that future generations can see, touch, and ride—a true legacy for our town.”

Following the Newman Historical Society’s meeting about reclaiming or recreating California’s first motorized school bus,

I reached out to First Student, the transportation company that currently owns the vehicle, for comment.

Bobbie Hartman, Senior Director of Customer and Community Engagement for First Student, said the discussions in Newman were news to her.

“This is the first I’ve heard of a group working on trying to get the bus back,” Hartman explained. “The bus is still in great condition—it had just returned from being on display.”

Hartman confirmed that while the bus is largely kept in storage, it continues to be maintained and occasionally showcased at events.

She also acknowledged that Newman-Crows Landing Unified School District had reached out previously regarding the specifications of the bus, information that First Student is currently working on providing. “That’s something we’ve been addressing,” she said.

When asked about the possibility of the bus being donated or returned to Newman, Hartman said she could not comment, reiterating that it was a new topic brought to her attention.

For now, the bus remains in First Student’s possession, preserved as a piece of transportation history. Whether it may one day make its way back to Newman—the town where it all began—remains to be seen.